By Margaret Paton

Do you teach English out-of-field? It’s time to stomp and clap, says Dr Lucinda McKnight. As well, did you know you could feel ‘out-of-field’ as an in-field English teacher if you taught a text you weren’t comfortable with or didn’t really know well? It can happen!

Dr McKnight is a senior lecturer at Deakin University in Victoria, Australia focusing on pedagogy and the curriculum. Her award-winning research into curriculum design looks at its role in teacher identity, autonomy and professionalism, esp. in English. She’s an ARC DECRA fellow and former English teacher, published poet/writer, and award-winning playwriter, too. You can find out more about her: https://blogs.deakin.edu.au/genderandeliteschools/dr-lucinda-mcknight/.

One of her best-performing research papers is called Meet the Phallic Teacher – that’s a teacher of any gender who’s ever more compliant. It explores designing curriculum and identity in a neoliberal imaginary. She talks about that paper and her exploration into out-of-field teaching as an educational researcher with a background in English and history teaching.

Below is the lightly edited transcript of my interview with Dr McKnight, with the bold bits my favourite highlights – you can hear it on the Out-of-Field Teaching Toolkit podcast, if you prefer.

*

Host: So welcome back to the outfield teaching toolkit podcast today I have researcher Dr. Lucinda McKnight from Deakin Uni, and her claim to fame, I guess, with regard to the out-of-field teaching phenomenon is looking at it through the lens of teacher identity, autonomy and professionalism. And we might even talk about her being a fitness trainer as well because that might be useful to know, some tips there. So, hello Lucinda, and thanks for joining me.

So, tell me what is your interest in out of field teaching?

Lucinda: Well, my interest in out-of-field teaching was really sparked most recently by an invitation from Professor Linda Hobbs at Deakin University, who is a fabulous expert in our field teaching. And she really needed someone who was an expert in English teaching to join her consortium of experts in different learning areas to be able to reflect on the whole experience of out-of-field teaching.

So, it was Linda who most recently really got me into this, but I have been an out-of-field teacher in school myself. I was trained as an English and history teacher. I did a degree in English, but even at the outset, I did fine arts and straight history at university. And I just did a half year history subject in second year, which was changing concepts of, of women’s place in Australian society. So even e in my very initial training, I was sort of out-of-field in a sense, because I was a fine arts graduate doing history method and went into school and I was teaching Australian history, which I hadn’t really studied in depth, but then also I taught human relations. S

Host: So how would you define out-of-field teaching?

Lucinda: The most basic sort of definition of our field teaching is – teaching in an area that you have not done a major in and, and or have not done method studies in. By method studies, I mean, studies in the pedagogy of that area. But there are, I know, multiple definitions of out-of-field and multiple ways you can be out-of-field. An English teacher can be out-of-field, in field, so to speak, if they’re just teaching a text that they may not connect with, or not have any background in studying or know anything much about, they might feel out of their depth. And you know, just not confident.

Host: No, I hadn’t actually thought of that. So you could actually be experiencing out-of-field newness, even though you’re in field.

Lucinda: Yes. And that’s a phenomenon that’s, you know, described in the research as well being out-of-field, in field. So it’s quite different to boundary crossing where you’re, for instance, maybe teaching another humanities subject, which is kind of close to English.

Host: What does the average teacher misunderstand about out-of-field teaching?

Lucinda: If it was the average person, I would say, the average person doesn’t understand how widespread it is. And the average teacher will, based on the work that I’ve been doing recently with Linda and other colleagues at Deakin University, teachers probably don’t understand just how different the disciplines are from each other. It’s like the Johari Window – you don’t know what you don’t know. And from the discussions that we’ve had when we when we get a group of people together, and we’ve got a design teacher, science teacher, English teacher and a geography teacher, we find sometimes we just can hardly understand what we’re each saying to each other because we’re coming from such different perspectives, such different places really – different, fundamental epistemological, so knowledge-based underpinnings of what knowledge even is. I think the enormity of the difference between the disciplines is something that probably people in general and, teachers themselves, don’t necessarily know,

Host: How has your research delved into this out-of-field teaching space?

Lucinda: In particular, through the Victorian Association for the Teaching of English, I was involved in a project that they did there because they were having a lot of trouble. The education officer there was having trouble really supporting all these teachers who were ringing in and saying I’m having to teach English, but I don’t have an English background. And so they wanted to do an informal research project, it was more consultancy, to establish what they needed to do for their professional learning program. And they asked teachers in schools, what the English teachers in schools, and particularly faculty leaders, felt teachers coming into English needed to know. It was very interesting and that really sparked my interest in out-of-field teaching. The idea that so many students out there were experiencing English not being taught by English teachers and trying to improve the experience of students in those classes and the experience of the teachers teaching them – that for me – really interesting thing because we see this happen as well in maths, trying to upskill teachers who have to teach maths out-of-field and, and science.

Host: But, all this key information, key concepts, key pedagogy, we’re kind of retrofitting, but how come it’s not part of it, initial teacher education like to get a nice broad sweep of all of the subjects, or is that being too utopic?

Lucinda: There, there is really limited time in it. For example, in my unit that I teach [at Deakin University], senior English curriculum inquiry, we have one week on poetry. We have one week on teaching Shakespeare. So, the idea of being able to fit in other disciplines in an 11-week program like that is just not possible.

But I do agree with you that there could be something better done some kind of orientation to the potential of having to teach out a field. And how can people be better prepared to know how to handle it in a strategic sort of way.

Host: Definitely, because one of the other interviewees who’s an out-of-field teacher, currently, he’s just really enjoying this space. In fact, he doesn’t care that he doesn’t do any commerce studies in business subjects that he’s qualified for. And it’s his own personal learning journey. And he’s, he’s actually experiencing success, and others see him as successful. There are some really interesting journeys in this space.

Lucinda: That’s so true that it is not always a negative thing. Sometimes people enjoy that the diversity that it gives them in their teaching program. It’s down to how well-supported teachers are and how successful they are enabled to be in teaching out-of-field. For me, when with my teaching human relations, in my first year of teaching, I was identified by the school counsellor, as a teacher who had a really good rapport with students. And I was then selected to be trained in the team within the school, as a human relations teacher. That’s how they came up with it. They’re human relations teachers. I didn’t have a background as a psychologist and hadn’t done anything in my degree, or my teacher training, that was relevant. Through this training and support in the school with a very close team and sharing of resources, we met every week to discuss what we were going to do it was great. And it was a lovely and very rewarding experience. And I went on to teach that every year I was at that school. It was one of the highlights of my teaching.

Host: Okay, no worries. So, I did mention the beginning that you look at our full teaching through the lens of teacher identity, autonomy and professionalism. Why is it important to use these lenses?

Lucinda: My work is always to do with those things. That’s my specific sort of area in education research. And I think it’s really important here for me in English, because I’m interested in teachers’ autonomy in relation to curriculum design, teachers’ ability to design their own lessons, design classes that meet the needs of their students, and combating a very formulaic, top-down sort of approach to curriculum that has been unfortunately reinforced by the NAPLAN program, then the national aptitude testing and literacy and numeracy.

I feel that and know from my own research that teachers who have less experience are more impelled to use formulaic approaches to things like the teaching of writing. So, teaching kids to write in formulaic sort of ways, five-paragraph essays with only three body paragraphs – three ideas allowed; the topic sentence compulsorily at the top of the beginning of every paragraph and as a final sentence that links back to the topic and then even formulas for each sentence within paragraphs. Things that you have to do like you’re your final sentence for your introduction must mention the key ideas. As for the three body paragraphs, and it’s really had a huge impact on the teaching of writing in school.

So, I’m interested in ways that teachers out-of-field in English can gain a deeper understanding of what the subject is, which is the antithesis of formulaic sort of approaches because English is a very unsettled and contested sort of subject. It has strong post-structural influences in it.

With the idea of reader-response theory, and the idea that everyone reading a book will have a different potential response to it and will write a very different kind of essay that not this formulaic sort of approach. I’m coming back to the idea of why agency and autonomy are important ideas in relation to teaching out -of-field, because I think those teachers, in particular, are at risk of not having those things.

Host: So just if I could mention the Cal Newport, who’s, who’s known for his Deep Work book, and many other books, and his podcast, does talk about needing career capital before you become creative and kind of move on, you know, it’s sort of it’s aligned with that idea you must do something for 10,000 hours before you hit creativity. So, don’t these budding out-of-field teachers of English need to know the basics before they can kind of spread their wings and explore teacher agency and professional identity?

Lucinda: I think they’d certainly need to find that fish before they’re doing really probably dramatic sort of things because they need to understand the subject itself. But English is a subject that’s about creativity. And if you don’t understand that, from the outset, you’re potentially not encouraging the students’ creativity. Every art teacher and English teacher has got to be creative because that’s what they’re encouraging of the students. Such teachers don’t necessarily have to be creative in a kind of whiz bang, incredible imagination sort of way. I mean, creative in terms of being responsive to the students and responsive to their ideas and things and being able to go with those rather than teaching in very formulaic recipe, IKEA lockstep kind of ways, which is what they might feel that they need to rely on.

Host: Okay, because that’s interesting because I think of Eddie Woo, who’s the New South Wales Education Department maths ambassador, who originally wanted to do English in the humanities and ended up being kind of lured into maths teaching, and is brilliant at it. And he talks about the way English is taught is great. If English was taught as the way maths is, you would do grammar, grammar, grammar, all throughout until the end of year 10. And then finally, in year 11, and 12, you can do some interesting stuff. But you’re talking about is you’re kind of breaking my misconceptions that English teaching is all about creativity. I know the formulas are there, particularly being a primary-trained teacher, but yeah, they’re kind of like they’re there on the side. But the formulaic teaching you’re talking about sounds so constrictive.

Lucinda: Yes, it is. And it’s been identified in so many national reports and things by the state and territory governments, this influence that NAPLAN has had on teaching, even for people in field, let alone people out-of-field and all teachers want to do the right thing by their students. They’re very keen to do the right thing. So, when you have this whole NAPLAN industry to have pressure, it puts some enormous constraints on teachers.

Host: Definitely. Okay. So in your university profile, you mentioned post-structuralism, feminism and new materialist theory. Can you just briefly outline what these are and how they connect with your view of out-of-field teaching? Or is that a question for a 4000-word answer?

Lucinda: I’ll just try and give a quick a quick answer here. Feminism is thinking with gender thinking – that gender and the way concepts and people and everything in the world is, gender thinking with that at the forefront of critique. My belief is that education is a highly gendered field. And that very formulaic approach is linked to a masculinist paradigm where everything can be measured. It’s all about benchmarks. It’s not about creativity, or emotion or empathy, or, you know, post the more personal growth type paradigm of English because that’s devalued as being more aligned with the feminine. Well, you know what is socially constructed as the feminine, the feminist angle looks at asymmetries of power in education and teachers, the teachers’ capacity to have power and to be treated as professionals in their discipline.

Host: Just on the feminist theory, I’m wondering, is there much appetite within the out-of-field teaching research space to look at how those responsibilities to teach out-of-field fall between the genders? Are they issues?

Lucinda: I think people would be very interested in that in that data, but I’m not aware of anyone looking at it that there may well be I think that would be fascinating.

Host: And new materialist theory, is that something you’ve mentioned with NAPLAN?

Lucinda: New materialist theory is something that I haven’t used so much in this out-of-field space, but it’s about thinking about matter as being just important in the world as words and discourse and ideas.

Host: Okay, and post-structuralism?

Lucinda: So post-structuralism is that notion of things not being neatly tied up in a box. And this is something that comes out a lot in the discussions with maths and science teachers, that English and the study of literature and things like that don’t necessarily tie up things in a box. Sometimes works of fiction are asking big questions that there aren’t necessarily easy answers to, and answers are proposed, but not necessarily settled. It’s not like you can take everything right and wrong, like you can maybe more in other in other disciplines, or that though, that probably is quite a crude understanding of other disciplines as well.

Host: One question I’m thinking about is, in terms of your academic research within the out-of-field space, what is the one [research paper] and finding that keeps getting cited?

Lucinda: I think I’m too new to this for my out-of-field work. I’m yet to be cited yet. But one of the articles that I’ve written that is cited the most is one called ‘Meet the Phallic teacher’.

It’s about curriculum and identity and a neoliberal imaginary. So, it’s this idea of a phallic teacher being a teacher who is like, there’s a British academic called Angela McRobbie. And she talks about the phallic girl who, who becomes ever-more highly feminised, even though she’s allowed to participate in the workplace, and in the economy more than ever before. But in order to do that, it’s a trade off, she has to have these really long fingernails, and really high heels and all this kind of stuff. So it’s a hyper feminizing, in adapting that for the concept of the phallic teacher, I’ve sort of described it as being the teacher today has to be evermore compliant. There’s almost a frenzy of compliance with requirements with all this administrivia with randomized control trial-based guidelines for how to teach having effect sizes for every little thing you do in the classroom. There’s this frenzy around compliance. And so, the article explores that idea and explores in what is a feminized profession, teaching as a feminized profession. So, whatever gender you are, as a teacher, you can still perform this kind of phallic teacher of, of compliance with all of the different layers, and layers of authority above you, rather than being respected as a professional in your own right.

Host: And in my own kind of writing, this is more in mainstream journalism, about teaching, I keep seeing an alignment with teaching as a caring profession as a public service, like nursing, another profession having the same issues of staff shortages, overwork. I’m wondering whether your work looked at those and describe teaching as a caring profession, or is that perhaps going a bit too far?

Lucinda: No, I don’t think there’s any, any argument that teaching is a caring profession, and that’s why it’s so undervalued. But for me, with my feminist sort of hat on, it’s because it’s aligned with caring work in the home. And there are plenty of other theorists since the 1980s, who have written a lot about that. So nursing and teaching are feminised professions, and fundamentally they’re undervalued and they’re simply not paid enough. That’s why there’s a shortage of teachers. It’s so interesting. It’s not rocket science. If you want to get more people to do teaching you to pay them more. You know, someone who comes through a degree and at the end of their degree, they can be a teacher or they can choose to earn maybe $200,000 or $300,000 more (over their career) if they go into another profession, where’s the choice? I’ve got two kids myself who are in senior levels of school. And, you know, I’m having a lot of these sort of conversations about career choices. Teaching is just not valued enough. Look at the early childhood sector. And what’s happening now we’ve got an incredible shortage of people there, we just don’t pay our value at enough.

Coming back to out-of-field, though, thinking about these things, I think it’s really important for out-of-field teachers to be able to inspire in students a real love of the subject, if we are going to have people who are going to end up as teachers. This really interesting question that you were mentioning earlier about how these teachers can get to the essence of the subject, but in a very short time, yes, it’s a tricky one.

Host: I do remember last years out-of-field teaching across specialisations symposium, the national Symposium. One of the speakers was talking about how to get to the essence, the key concepts. I must dig up that presentation and see if I can have a bit of a chat to him as well.

So, Lucinda, if you had an unlimited budget and time to do an out-of-field teaching research project, what would it be and why?

Lucinda: Well, I would love to develop an intensive program, pack set of resources, something that would support teachers coming to work out-of-field in English and trial it and see how it went as a bit of an action research project.

Host: Okay, that sounds great. But how does that become a good fit in the different contexts in schools across Australia, from the regional remote, very remote urban, inner city?

Lucinda: Ideally, it would be a massively funded project. It would involve schools and input from schools in all those different areas that we trialled. They’ll be something developed in collaboration with teachers allowing teachers leadership in the space, and then it will be trialled in a whole lot of different schools. And it will be something really accessible that teachers could use, whether it be maybe online or something so that if teachers found they had to teach you how to field, they would be able to just access it and with incorporating general principles of teaching out-of-field, such as the sort of work that I’ve been doing on doing at Deakin, like what, what do teachers need to know to be and do and that whole idea of the knowing, being and doing and how they’re different in different disciplines, but and then looking at specifically what that means in English, and then it would be a pack or something that could potentially be adapted for other subjects.

Host: Oh, excellent. No, I like that. I would be the first to buy or, or download that one. And I’m wondering whether you’re going to tap into social media, Twitter, the different Facebook groups to see what’s already out there, in terms of guidance, best practice? Or will it all be about fresh research, fresh interviews, and, and pulse groups, that kind of thing?

Lucinda: Well, in my in my dream project, there would definitely be a literature review stage that would look across all kinds of literature and media to see what was already out there. And build on what’s already good. But we’re in the Victorian Association for the Teaching of English, when we did that little bit of work, where we looked at what people were doing, there wasn’t anything really there, generally, for people to draw on. That’s why they were bringing up the office, people on the phone asking for help, ‘I’m having to teach English I’m having to teach Frankenstein or whatever it might be, and I just don’t know where to start. What can you do for me?’ So yeah, this and subject associations would be involved in this in this project because I think they’re really they’re at the frontline of trying to support out-of-field teachers.

Host: What is the most interesting piece of that field teaching research you’ve come across? And why?

Lucinda: Well, I’m biased, but I’m really, really just so fascinated by the work that we’re doing at the moment with the different disciplines coming together. It’s interdisciplinary work on out-of-field because I think there’s nothing like speaking to people in the other disciplines to highlight the essence of your own discipline and enable you to articulate it for other people, and the misunderstandings that have occurred between us as a group and the kinds of the words that people who are in science and maths will be using to each other to describe their work. And I’ll have to say, hang on, we don’t even use that word in English. What does that mean? And that’s been absolutely fascinating. And I’ll just give you a little example from this. At one of our discussions when I described a poetry lesson I went to observe that a teacher, a pre service English teacher was teaching at Deakin. And she did a lovely lesson. It was a fabulous … a fabulous choice of poem. And but I had to say to her at the end, but we didn’t hear any poetry, the kids just read the poem off the sheet, and then answered the comprehension questions. Poetry is designed to be heard, and anyone who studied literature knows that that poetry is meant to be listened to. So that was a good example of something that could very readily be done by an out-of-field teacher who might not have that disciplinary background knowledge. And the other people in the group would say, ‘no, we would never have even thought of that we would have just had people read the poem and, you know, often on the sheet and do their answer their questions’.

Host: Good point. Yeah. Because so many of us can remember our own school years when the teacher would randomly pick students to read out aloud. And the poor dyslexic students who could not read, that would have been torturous. So, I’m wondering whether they’re kind of trying to avoid that anxiety in class by not getting kids to read out the poem.

Lucinda: But, it has to be modelled as well, because you don’t just read it out – it’s got to have pauses. It’s a performance. The whole question of whether to read aloud whether to force kids to read aloud, the teachers and the skill of the teacher in reading aloud and giving a really, as you say, really lively and beautiful reading of the poem. The English teachers in pre service education, we talk to them about their own performance, a performative sort of reading in the classroom. We give them practice and all that kind of thing. But if you’re coming from out-of-field, you won’t have any of that. It’s just an example of one of those things that you might not even realise you don’t have. Everyone probably gets kids to read things out in class, but you might not have that background in the aesthetics of reading aloud and the performative angle of it.

Host: And I’m thinking, you know, the sheet, should you be lucky enough as an out-of-field teacher to be left a lesson plan? I’m pretty sure the substantive teacher is not going to say, make sure you read out the poem, because it’s going to seem like you’re telling him to suck eggs. So yeah, you’re not going to get that lovely detail, that crucial detail to make the class come to life.

Lucinda: Yeah, it does seem like you’re teaching them to suck eggs, but also you just don’t have time when you’re leaving standby lessons, or those kinds of lessons. You don’t have time to write out instructions at that sort of level.

Host: Yeah, exactly. Okay, so I’m wondering if Australia is perhaps leading the way in out-of-field teaching, research, and teaching. What do you reckon?

Lucinda: Yes, once again, I think I’m probably biased, but I think we are doing a great job. And that the out-of-field symposium that we held last year is a great example of the work that we’re doing to really foreground this phenomenon and, and get people talking about it and get all sorts of different people talking about it. You know we had, we had subject associations, we had principles, we had policymakers, we had all sorts of different people coming together and talking about this as something that really needs attention and discussion and support because of the teacher shortage, which we all know that we’re facing. I think this week [August 2022], there’s a big meeting of the ministers of the states and territories of education to talk about what on earth is going to be done about the teacher shortage? Well, the teacher shortage has an impact out-of-field as well, because a shortage of teachers in field means that people are going to be forced to teach out-of-field.

Host: Yes, exactly. So I’m just that we’re doing this interview on the eighth of August 2022. Okay, so should we all get used to the idea that all teachers will have to teach out-of-field teaching regularly? And do you reckon is that a good thing?

Lucinda: I think all teachers are going to have to teach out-of-field because even just as you’ve described, when you take someone else’s lesson when they’re away sick, you’re teaching out-of-field. It’s really important for us to start to acknowledge this, although we could we call it a phenomenon as if it’s something unusual. Teaching out-of-field is an ordinary part of teachers’ everyday work at that basic level. Then there’s what we’ve discussed today, the idea of being out-of-field infield, when you might have done a literature degree, and then being told you’ve got to teach how to write a rolling news blog. So that you’re out-of-field in field. And then of course, there’s the thing where someone just says to you we know you’ve been teaching for 20 years, but I think you mentioned you had done a first year French subject. At uni, well, we want you to teach French next year, we’re desperate. I think it’s going to land in people’s laps more and more often.

Host: It’s such a shift because I don’t know if you remember this, but about five years ago, there was a federal parliamentary committee, a Senate committee that looked at productivity and innovation. And they actually had as one of the recommendations that by June 2022, out-of-field teaching of STEM would not occur. So, it didn’t get on. The minister’s education ministers didn’t even look at it. I spoke to the chair of that committee, and he said, yeah, that’s what had to happen. That didn’t happen. But obviously, up at that policy level, they’re saying, oh, it’s an issue. But day-to-day teaching, it’s like, it’s just, it’s just got to happen. There’s just got to be out-of-field STEM teachers, it’s the only way schools can operate, the way the system operates.

Lucinda: That’s so true. At the Victorian Association for the Teaching of English, we had a really interesting discussion, at the point when we started talking about how many calls we were getting for supporting out-of-field. And we said, do we want to support this? Do we actually want to have resources and conferences and things for out-of-field teachers because that’s not our key remit? Even as a subject association, it’s to support our members who are largely in field. And do we want to be seen to be encouraging this? Do we want to be seen to be making out hat it’s a good thing?

Host: What did you decide?

Lucinda: In the end, it was about the students … wanting the students to have the best possible experience of the subject across Victoria. So, we decided yes let’s go for it. Let’s support them in whatever ways we can, and encourage them to be involved in a subject association, an important resource for teachers.

Host: Okay, so I did mention a bit out-of-left field that you’re also into fitness training; you’re a qualified fitness trainer. Is there a connection between that and out-of-field teaching? Can we make one?

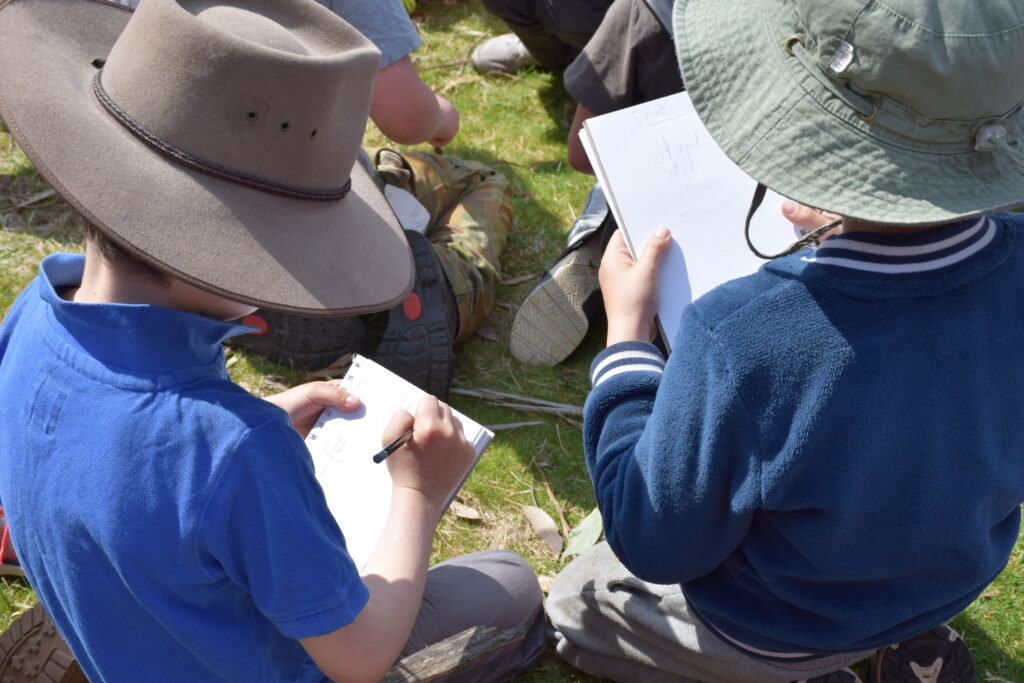

Lucinda: Yeah, definitely. Another really big thing for me is thinking about movement in the classroom, incidental movement in the classroom, and how in English pedagogy, people can be putting in opportunities for students to stand up and move around and use their bodies in all sorts of different ways. And, so, for infield teachers who have had training in that sort of thing and their discipline, how to, for example, just off the top of my head, doing a gallery walk, where you get kids to put up their posters or little pieces of writing that they’ve done on the wall, and everyone gets up in the corridor and walks up and down and looks at them. That’s just one example of many, or learning grammar through your body. So, learning I’m doing I don’t know if you can hear me stomping, I’m doing a stomp here, doing different stops and claps and things to learn the stresses in punctuation, like stops and semicolons. If you’re out-of-field, you are potentially teaching in ways that don’t use the incidental movement that you can build into your classes, and therefore you might be giving more static classes out-of-field. And so that’s a real concern as well.

Host: Okay, yeah. I know there’s a movement called Brain gym, and it’s all about movements. But I think in some way that’s been disproved. But I know that particularly in primary school classes, you’ve got to get the kids up and moving, you know, floor time, back to your seats, group table. Let’s have a stretch. Let’s just do a circle. Even with maths, we bring our hands into play. Just trying to think of an English analogy. Yeah, but the clapping, definitely the clapping for the syllables. We do that quite a bit.

So we’ve had a lovely wide-ranging talk here about outfield teaching, but about your research, your wish list, anything else you’d like to have a chat about to do with out-of-field teaching?

Lucinda:, I really think it’s a very, very important phenomenon for us to be talking about. It would be great if schools themselves were more explicit about teaching out-of-field and had more, did more to support teachers teaching out-of-field, which is something that I think could be done quite readily, even if we just talked about it more, more openly and obviously, but for many schools, it’s quite hidden, because schools don’t want parents to know about it yet, so they don’t make a big, big deal about it. And then, unfortunately, means that it’s not supported in ways that it could be. So we need to get it out there. We need to talk more about what you were saying earlier. The benefits of teaching out-of-field for teachers and for students to that they can get fresh perspectives if it’s adequately supported differently.

Host: Now, I like that idea about the psychological noise that the shame and the guilt of out-of-field teaching and like last week, going into a class and you know, and hearing ‘Miss are you a real teacher, what do you really teach? What’s your real subjects?’ I hope that maybe one day kids can value and parents can value out-of-field teachers as much as infield teachers but as you say, crucial to that is system wide and down to context, school context, support, and mentoring is lovely. Thank you for your time today.